On May 12, 2021, U.S. President Biden signed the highly anticipated Executive Order (EO) on Improving the Nation’s Cybersecurity (and the government issued a fact sheet summary of the contents). U.S. Presidents use Executive Orders (EO) to provide guidance to federal agencies as part of enforcing laws passed by Congress and managing the executive branch of the U.S. Government. This EO is the most detailed ever issued on the topic of cybersecurity in the nation’s history. It has global implications because of the size of the U.S. Federal Government and its purchasing authority for cybersecurity solutions – estimated to be nearly $20 billion annually.

The cybersecurity industry has been expecting action from the U.S. Federal Government, especially in the wake of the SolarWinds attack in late 2020 and the recent ransomware attack on Colonial Pipeline that caused a major disruption in the fuel supply. Now that the order has been released with detailed guidelines and aggressive timelines for action, there are many questions about what it means for Federal Government, state and local governments, the private sector, and IT security professionals.

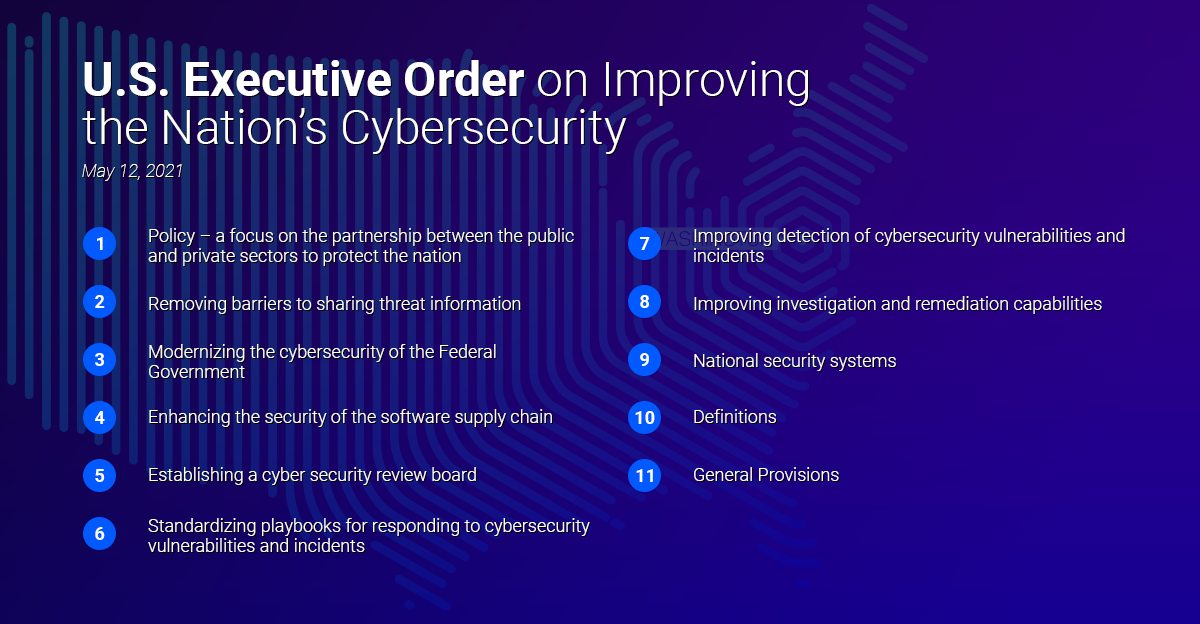

The EO is broken into 11 sections:

This blog will discuss the first nine sections and provide analysis in a hype-free manner, but we encourage everyone to also read the EO and Fact Sheet directly to reach their own conclusions.

Section 1. Policy – A Partnership Between the Public and Private Sector to Protect the Nation

From the outset, the intent of the EO to not only influence the U.S. Federal Government but also the private sector is clear. This section lays out the aims for the EO; namely, “to identify, deter, protect against, detect and respond” to “persistent and increasingly sophisticated malicious cyber campaigns that threaten the public sector, the private sector, and ultimately the American people’s security and privacy.”

This section continues with a need to “carefully examine what occurred during any major cyber incident and apply lessons learned” and that this requires the Federal Government “to partner with the private sector.”

Questions raised about what will be considered a major cyber incident

What exactly defines a major cyber incident? Here the EO makes reference to a separate government memorandum, the Presidential Policy Directive – United State Cyber Incident Coordination, issued in July of 2016. This directive states that a significant cyber incident is either an individual or “group of related cyber incidents” that are “likely to result in demonstrable harm to the national security interests, foreign relations, or economy of the United States or to the public confidence, civil liberties, or public health and safety of the American people.” This definition leaves significant room for interpretation. For example, the recent ransomware attack on Colonial Pipeline, which disrupted the delivery of fuel to the U.S. East Coast, most certainly qualifies under the definition. But what about the cyber-attack on the Oldsmar water treatment plant in Florida that impacted a local population of 15,000? Looking beyond critical infrastructure, does a large data leak like the release more than half a billion users’ phone numbers and other personal data from Facebook invoke the EO’s provisions?

A call for transparency in private sector cybersecurity products

Section 1 on Policy also declares one of the EO’s aims is to “ensure its [the private sector’s] products are built and operate securely” and that “the trust we place in our digital infrastructure should be proportional to how trustworthy and transparent the infrastructure is…” and that such trust extends to computer systems “whether they are cloud-based, on-premises, or hybrid.” These statements have the potential for the most far-reaching aspects of the EO. The call for transparency in private sector cybersecurity products has both positive and potentially negative consequences as openness provides the opportunity for better understanding of risks by government agencies and IT cybersecurity professionals. But it also provides opportunities for malicious actors as they will have more visibility into technology being used by Government agencies.

Section 2. Removing Barriers to Sharing Threat Information

This has been an objective within the government and the cybersecurity community, and, to a certain extent, has been realized through initiatives such as the U.S. National Vulnerability Database; cybersecurity message boards, events, and social media; and commercial threat intelligence offerings. The EO calls for removing contractual barriers and increasing the sharing of information about threats, incidents, and risks to improve incident deterrence, prevention, and response efforts. It puts pressure on government agencies to act within 60 days to review and update contract requirements so that service providers collect and preserve data relevant to cybersecurity events, share that data and collaborate with Federal cybersecurity or investigative agencies in their responses to incidents or potential incidents. Additionally, it asks technology and service providers to “promptly report to such agencies when they discover a cyber incident involving a software product or service provided to such agencies.”

Technology and cybersecurity vendors will need to standardize on EO provisions

Vendors will have an incentive to standardize contract language and reporting requirements across all customer relationships with the provisions of the EO setting a new minimum standard for information sharing. Notably, the EO does not address the fact that threat intelligence is commercially-valuable and while sharing threat information about an incident related to a vendor’s own software products (such as in the SolarWinds hack) is likely to be seen as governed by the EO, what about security disclosures vendors may identify about other vendors’ software and services?

Section 3. Modernizing Federal Government Security

In this section “Zero Trust” has its day. Security experts have called on the Federal Government to update its systems and processes and “modernize” security to meet the changing threat landscape. This section focuses on the concept of Zero Trust Architecture, acceleration of Federal computing to “secure cloud services”, the centralization and streamlining of access to “cybersecurity data to drive analytics for identifying and managing cybersecurity risks”, and investment “in both technology and personnel to match these modernization goals.”

The term “Zero Trust” was first coined by analysts at Forrester Research more than 10 years ago. They heralded the EO as “amplifying what we have known for a long time: Zero Trust works. And now, the U.S. federal government has validated, confirmed, and required Zero Trust.”

Zero Trust Architecture is based on an acknowledgement that threats exist both inside and outside traditional network boundaries. Traditionally applied more heavily to security access management, the Zero Trust section of the EO references allowing “users full access but only to the bare minimum they need to perform their jobs.” Zero Trust also extends to devices and workloads as access is not only governed at a user-level but also through APIs, and shared resources running on the same virtual and physical hardware, which can be used to gain access to sensitive applications, systems, and data through lateral movement and other cyber-attack methods.

This section continues with a requirement for Federal agencies to “adopt multi-factor authentication and encryption for data at rest and in transit” within 180 days and calls on the Director of CISA (the US Cybersecurity Infrastructure and Security Agency) to “establish a framework to collaborate on cybersecurity and incident response activities related to…cloud technology” within 90 days. Considering the significant budgetary implications for these provisions, it remains to be seen what the cost will be, how or if this will be funded from existing Federal agencies budgets, or if new allocations will need to be made by Congress.

Section 4. Enhancing Software Supply Chain Security

The SolarWinds hack has been a significant wake up call to the risks of compromise in third-party software and services that can be used to breach an organization’s networks and systems. The EO states that “development of commercial software often lacks transparency, sufficient focus on the ability of the software to resist attack, and adequate controls to prevent tampering by malicious actors.” Accordingly, the EO calls on the Director of NIST, the US National Institute for Standards and Technology, to quickly (within 30 days) solicit input from the Federal government, private sector, and others for the purpose of identifying existing (or developing new) standards, tools, and best practices to evaluate software security and to publish preliminary guidelines. These guidelines are expected to include stringent requirements around secure software development to demonstrate compliance and ongoing checks “for known and potential vulnerabilities” and the remediation of them, including “making publicly available summary information on completion of these actions.”

Vendors must supply a “Software Bill of Materials (SBOM)”

The EO specifies that vendors must supply a “Software Bill of Materials (SBOM) for each product directly or by publishing it on a public website” and must participate “in a vulnerability disclosure program.” What adds significant weight is the requirement that the Director of CISA “shall identify and make available to agencies a list of categories of software and software products” that meet the definition of “critical software” (to be defined within 45 days of the EO). Given that many software products require elevated privileges to communicate across systems, there is high potential for not only IT monitoring and cybersecurity products but also many business applications to fall under this definition.

With the EO stating that “software products that do not meet the requirements” must be removed, these provisions have wide-reaching implications for improving the supply chain security of software products, but also bring significant potential risks to vendor costs as well as disclosure of potential vulnerabilities and risks which may not have been known to malicious actors. It is worth noting that the EO extends the requirements to “legacy software” as well as specifically to “Internet-of-Things (IoT)” devices. No doubt there will be significant debate regarding how far these provisions will extend and the EO anticipates the need for case-by-case “extensions” and even “waivers” for agencies that have difficulty complying with the requirements.

Section 5. Establishing a Cyber Safety Review Board

The EO calls for the creation of a Cyber Safety Review Board (CSFB) to “review and assess…significant cyber incidents” (as defined previously above). Of note, the Board will include both Federal officials and private sector representatives and will be required to “protect sensitive law enforcement, operational, business, and other confidential information that has been shared with it…” the CSFB provides a significant opportunity for increased disclosure and collaboration between government and private sector on cyber incidents, however, with the increasing frequency of such incidents and a vague definition for what might constitute a significant cyber incident, there is the risk of the Board quickly bogging down, taxing already limited resources in government and for-profit software and technology enterprises.

Section 6. Standardizing the Federal Government’s Playbook for Responding to Cybersecurity Vulnerabilities and Incidents

The EO raises the concern about inconsistent practices for responding to cybersecurity vulnerabilities and incidents across federal agencies and calls for the Director of CISA along with other agency heads to develop “a standard set of operational procedures (playbook) to be used in planning and conducting a cybersecurity vulnerability and incident response activity…” including the potential to “recommend use of another agency or a third-party incident response team as appropriate.” We believe this effort holds significant potential for the refinement of established best practices for incident investigation and response, and appreciate the government’s acknowledgement that third-party incident response teams can play a vital role in helping coordinate investigations and remediation.

Section 7. Improving Detection of Cybersecurity Vulnerabilities and Incidents on Federal Government Networks

As a logical continuation of the previous section, the EO calls on the Federal Government “to maximize the early detection of cybersecurity vulnerabilities and incidents on its networks” including the use of “Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR)” solutions, along with “active cyber hunting”, “containment and remediation”, and “incident response.” A new “EDR initiative” will require agencies to adopt a Federal Government-wide EDR approach. EDR solutions have demonstrated significant value in cybersecurity prevention, detection, and response on endpoints, limiting their propagation across networks to other systems, and this new initiative shows how vital these solutions will be in improving the Federal Government’s cybersecurity defenses.

This section of the EO also addresses the need for cyber threat hunting activities including that such efforts “ensure that mission-critical systems are not disrupted”, there are “procedures for notifying system owners of vulnerable government systems, and the range of techniques that can be used…” This language is welcome as threat hunting has proven its value in identifying malicious actors that have breached network and other defenses. What is potentially risky, however, are limitations on what methods may be used as implied in the EO language. Also not addressed are the resources necessary for threat hunting operations, which typically require advanced cybersecurity analysts that are in short supply. It is likely a public-private partnership of a commercial nature will be necessary to meet this demand.

Section 8. Improving the Federal Government’s Investigation and Remediation Capabilities

Much of this section focuses on the importance of collecting and maintaining network and system logs, calling on the Secretary of Homeland Security in consultation with other agencies to define “requirements for logging events and retaining other relevance data within an agency’s systems and networks, “including “the types of logs to be maintained, the time periods to retain the logs…and how to protect logs” using “cryptographic methods.” As with other cybersecurity technologies and methods discussed above, we applaud the EO’s call for more specific requirements regarding logs as they are invaluable to incident investigation and remediation. However, as with other cybersecurity capabilities, agencies will require not only resources to purchase and implement technology solutions for log management but also personnel to manage them and introspect such logs. The Federal Government must be prepared to make such investments either with agency personnel or contract resources for the provisions in this section to be realized.

Section 9. National Security Systems

This section deals with systems classified as National Security Systems and the need to adopt “requirements that are equivalent to or exceed the cybersecurity requirements” set for in the EO “that are otherwise not applicable to National Security Systems.” This allows for “exceptions in circumstances necessitated by unique mission needs” and the EO calls for these requirements to be “codified in a National Security Memorandum (NSM).” The EO specifically states the provisions contained in the EO will not apply for National Security Systems until the NSM is issued and there is no timeline given for the issuance of the NSM. While understandable that some exceptions may be necessary for National Security Systems, this significantly weakens the near-term implementation of the EO for systems that are classified as National Security Systems, which are of high interest to malicious actors.

Conclusions

The expansive nature of the EO indicates many of its provisions were in development for some time. The recent SolarWinds hack and Colonial Pipeline incident likely elevated the perception of risk within government, resulting in an expedited release. As mentioned, we commend most actions called for in the EO, including the need to budget not only for technologies but personnel to assist Federal agencies in complying with them. However, by the very nature of its breadth, the EO does likely face significant challenges in its implementation.

The cost to implement the EO will be immense and have far reaching implications

A major issue the Federal Government will encounter is the cost to implement the various recommendations in this EO. The Director of OMB (the US Office of Management and Budget in the executive administration) is instructed to include “a cost analysis” in the annual budget process for these items. In his analysis of the EO, Analyst and former Fortune 500 CISO, Ed Amoroso, takes a dim view, saying it is, “well intentioned” but “too long and includes far too many unattainable goals.” Instead, he suggests that the money and effort would be better spent “demanding that every company in the Fortune 500 sponsor ten students for a free computer science BS degree in return for five years in the government.”

Security staffing shortfall will become even more critical

There continues to be a massive shortfall in the number of qualified cybersecurity professionals with many estimates concluding that there are at least three million more jobs globally than there are individuals qualified to fill them. With government jobs often paying less than private sector positions, it remains to be seen how successful the Federal Government will be in attracting such a limited pool of talent for the likely thousands (or more) cybersecurity positions that the EO will require for implementation. This will put even more pressure on private sector organizations already competing for such scarce talent and could be a catalyst for more organizations moving to Managed Detection and Response (MDR) services where vendors provide 24×7 cybersecurity monitoring and incident identification when organizations cannot or choose not to staff this capability themselves.

Despite the questions raised, the EO is already increasing serious industry dialog regarding how we can collectively better protect our systems across government and the private sector. We at Bitdefender look forward to playing a key role in that dialog as a provider of cybersecurity solutions to tens of thousands of businesses, government entities, and non-profits and millions of consumers worldwide.

— The Bitdefender Business Solutions Group Team