Elon Musk’s takeover of the company might bring a swathe of changes to Twitter, including the introduction of end-to-end encryption for direct messages (DMs).

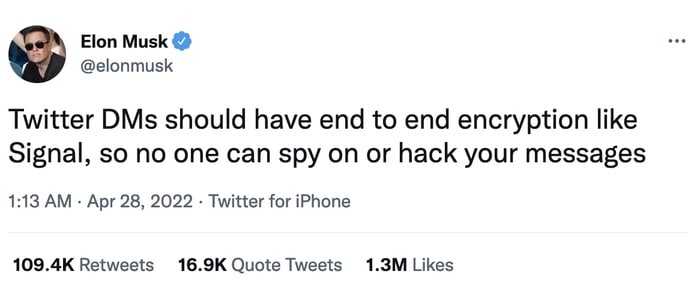

Musk, in customary fashion, tweeted his opinion to his many millions of followers.

Twitter DMs should have end to end encryption like Signal, so no one can spy on or hack your messages

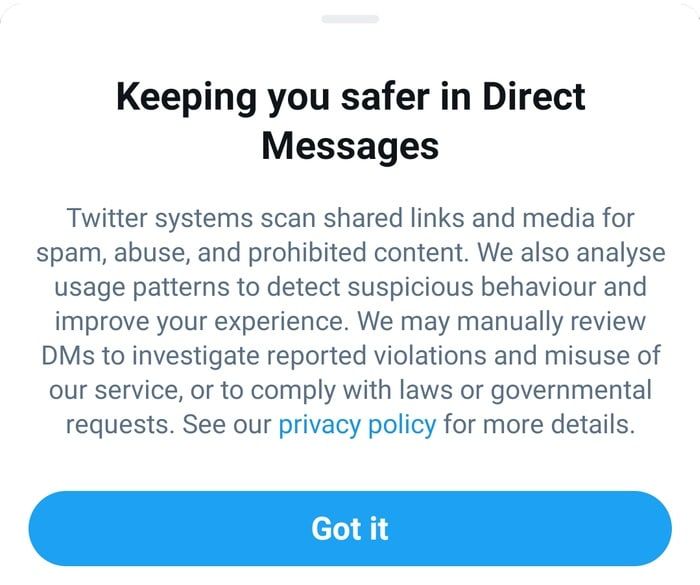

Whereas messaging apps such as WhatsApp, Signal, and iMessage allow their users to send private messages to each other, Twitter DMs are readable by Twitter before they reach their recipient.

Twitter doesn’t make any secret of this processing, saying that it scans DMs for prohibited content (such as spam), and can even have its workers manually review DMs when investigating if the service is being abused, or to handle requests from law enforcement and governments.

But the perception for many Twitter users is probably that a message sent by DM is only going to be read by its intended recipient. That means users might be inclined to share private, sensitive information that they might be wiser to share via a more secure communication system.

Musk isn’t correct that “no-one can spy on or hack your messages” if Twitter DMs were to become end-to-end encrypted. After all, if anyone had access to (or hacked) either the sending or receiving accounts, they would be able to read the messages as simply as the genuine correspondents.

But end-to-end encryption does make it more complicated to scoop up a person’s private messages, particularly if you – like an authoritarian regime or over-reaching intelligence service – wanted to surveil a large number of users.

If, under the rule of Elon Musk, Twitter does in the future introduce end-to-end encryption for DMs it will need to think carefully about the impact it might have on abuse of the messaging service.

I imagine that users would still be able to report individual DMs they receive – sending their content to Twitter’s security and safety teams for investigation – but it will still be keen, I would imagine, to prevent dangerous links or abusive content from being sent in the first place.

Twitter will also find itself up against governments who are concerned that end-to-end encryption might stymie their efforts to fight crime.

The UK Home Office, for instance, is spending millions in a campaign that asks tech companies to not roll out end-to-end encryption until “they have the technology to ensure children will not be put at greater risk as a result.”

In the past they have even attempted to argue that “real people” don’t want secure communications.

In my opinion, encryption isn’t a bad thing. It’s a good thing. Encryption protects our privacy from hackers and organised criminals. It defends our bank accounts, our shopping, our identities, our private conversations. And it saves the lives of human rights activists working against oppressive regimes.

Yes, encryption can be used by bad people as well as good. But that doesn’t mean that good people should not have the opportunity to be protected by it.

As James Ball of the Bureau of Investigative Journalism once said:

“The real-world analogy to the Home Office’s attitude to encryption is as if the police campaigned to ban door locks because they made it harder for police to get into criminals’ homes.”

And if Twitter does introduce end-to-end encryption, it won’t be the first time the service has flirted with the technology. Back in 2013, Twitter was reportedly working on introducing the feature for DMs in the wake of Edward’s Snowden’s revelations about NSA monitoring, only to later quietly drop its plans.

My hope is that Twitter will introduce end-to-end encryption in the fullness of time, just as it has introduced other security and privacy features over time to better protect its users.